[5th post in a series; start with the first post here]

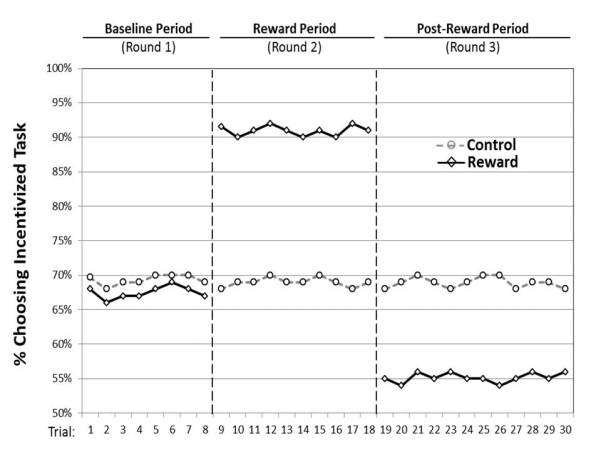

This week, I’ve talked about the controversy over whether or not incentives reduce intrinsic motivation, leading to less task engagement than if the incentive had never been offered. Yesterday, I covered Indranil Goswami’s research with me, which tests this idea in repeated task choices, and finds that the post-incentive reduction is brief and small (relative to the during-incentive increase).

So, what does this mean for the original theories? Remember, paying people was supposed to feel controlling and reduce autonomy and therefore supplant people’s own intrinsic reasons for doing a task.

Maybe the theory is mostly right, just wrong about the degree and duration of the impact it has. Maybe intrinsic motivation is reduced, but bounces back after giving people a little time to forget about the payment. Or maybe giving people the opportunity to make a few choices on their own without any external influence resets their intrinsic motivation.

But maybe the theory is just wrong about the effects of payments. Perhaps people are trying to manage the eternal tradeoff between effort and leisure over time. If they want a mix of both effort and leisure, then when they have a good reason to invest more in effort for a while, they do. But then, when the incentive is gone, it’s an opportunity to balance it back out by taking a break and engaging in more leisure.

For research purposes, it’s helpful that the Deci, Ryan and Koestner paper is quite clear about the theoretical process. This can be used to make predictions about how motivation should change depending on the context, according to their theory. Indranil designed several studies to test between these accounts.

In one study, he gave people different kinds of breaks after the incentive ended. He found that giving people a brief break eliminated the initial post-incentive decline, but only if the break did not involve making difficult choices. So, it doesn’t seem like giving people the opportunity to make their own choices took away the sting of controlling incentives, making the negative effects brief. Instead, it’s that giving people a little leisure made them willing to dive back into the math problems.

But how about a more direct test? The intrinsic motivation theory predicts that the negative effects of incentives should be more pronounced, the more intrinsically motivating the task is. If I really enjoy watching videos, and you destroy my love of video-watching for its own sake with an incentive, my behavior afterwards when there is no incentive should be really different. On the other hand, if the post-incentive decline is because I was working hard during the incentive and need a break, then I should be less interested in changing tasks after being paid to do an easy and fun task.

To test this, Indranil took his experimental setup and varied which task was incentivized, paying some people for every video they watched in Round 2, and others for every math problem they solved. After being paid to do math, when the payment ended, people wanted a break and initially watched more videos for the first few choices. But after being paid to watch videos, when the payment ended, there was no difference in their choices, contrary to the intrinsic motivation theory.

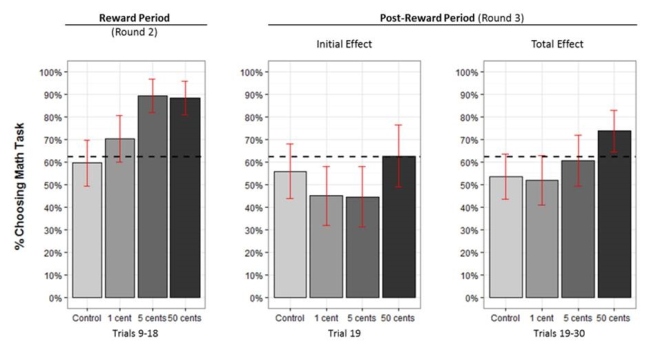

Perhaps the most direct test came from simply varying the amount of the payments, in another study, either 1 cent, 5 cents or 50 cents per correct match problem in Round 2. According to the intrinsic motivation theory, the larger the incentive, the more controlling it is, and the more damage is done to intrinsic motivation. However, if people are balancing effort and leisure, they may feel less of a need to do so, the better they are paid. As the chart below shows, paying people a high amount (50 cents) lead to not only no immediate post-incentive decline, but summing across all of Round 3, people did more of the math task without any additional payment. Again, the opposite of what the intrinsic motivation account would predict.

So, what does it all mean? We need more research to figure out when it is that incentives will have no post-incentive effects, a negative effect or a positive effect. But at a minimum, our findings strongly suggest that simply offering a temporary incentive does not necessarily harm intrinsic motivation. Instead, it seems that when an incentive gets people to work harder than they would have otherwise, they just want to take a break afterwards.